On Shakespeare’s Ophelia

By Carol McCluer

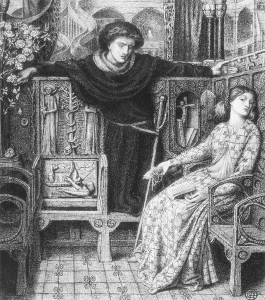

The title of the book, Reviving Ophelia, is a reference to the character of Ophelia in Shakespeare’s play, Hamlet; she is used as a symbol for what the author, Mary Pipher, says happens to young women. “As a girl Ophelia is happy and free,” she writes, but at adolescence “has no inner direction.” When she falls in love with Hamlet, she “lives only for his approval” and “struggles to meet the demands of Hamlet and her father…[T]orn apart by her efforts to please,” Pipher continues, “Ophelia goes mad with grief and drowns herself.”

Though this is the conventional way of seeing Ophelia, it is simply not true to the character Shakespeare wrote. In terms of acting the part of Ophelia, what a difference it’s made to have learned about this from Eli Siegel’s Shakespeare’s Hamlet: Revisited. Mr. Siegel is the critic who understood Ophelia truly, and he showed—looking with scrupulous and loving exactitude at the text—that the Danish girl is not a passive victim—in fact, she has active contempt, shown clearly through the lines Shakespeare has her say, and also through what she doesn’t say. Ophelia, Mr. Siegel explained, “has been seen too often as one sadly affected by other people’s doings.” But, he continued, “It is hard to be alive and not have motives.”

For example, when her father Polonius tells her she should rebuff Hamlet’s advances, and hides himself so that he can listen to their conversation, Ophelia—though she has said she loves Hamlet—willingly complies. When Hamlet rightly criticizes her deviousness, and asks her these two simple questions: “Are you honest? Are you fair?”—she doesn’t like it, is very hurt, and says he is crazy. “Ophelia is one of the least self-critical beings imaginable,” said Mr. Siegel. “If you are not self-critical, you can hardly be honest.”

The way Mr. Siegel sees and explains the motives of this young woman is what young women today desperately need to know, including the reason why Ophelia later loses her mind—and this is the very thing not seen in this book. Young women dislike themselves not because demands are made on them, or the approval of others is hard to get, but because the way they see the world and people is not fair, not deep or kind enough, and has too much contempt with it.

I saw that I disliked myself because, like Ophelia, with all my acting demure, I was also terrifically conceited, even deluded. I just assumed I was everything a man could hope for, and couldn’t understand why one relationship after another ended bitterly. I got tons of approval from men, and applause from audiences as a singer and actress, and still wasn’t happy, yet it never occurred to me that the reason could have to do with any injustice of my own.

The education I got in Aesthetic Realism consultations opened my eyes to the best things in myself, and also to why I despised myself. As I began to learn how to honestly, happily criticize myself—seeing myself in relation to art, other people, the whole world—I felt set free.

First presented in a public seminar at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation, New York City.