From an Aesthetic Realism Public Seminar

William Macready—& What Men Can Learn about True and False Importance

By Derek Mali

The beautiful and necessary education of Aesthetic Realism, founded by poet and critic Eli Siegel, enabled me to criticize my contempt and freed me from being separate, aloof, and snobbishly unhappy. My gratitude to Mr. Siegel is unbounded because he showed that our true importance is in keeping with our very purpose as human beings—to like the world, see meaning in it.

This explanation is magnificent. And it is so different from what I grew up thinking: that the thing that made me important was our illustrious family name and our modest, dutiful, unassumingly superior manner. I had spent most of my early life using the persons I was closest to against other people, and I went for fake importance at the expense of my own happiness. Tonight I will speak on what I learned from Aesthetic Realism about true vs. false importance, including in the life of the renowned English Shakespearean actor, William Charles Macready.

I. Aesthetic Realism Explains False Importance—and Its Attraction

I was raised in a five-story town house on Manhattan’s East 69th Street, with two maids, a cook, governesses, and an assumption from as early as I can remember that the Malis were of a decidedly higher realm than the majority of people. The wealth and background of my family made snobbish importance seem a quiet fait accompli. Meanwhile, the effect of this “importance” on my life was deadly: I felt lonely, and painfully separate from people around me. During many of my ten-day spring vacations from prep school and college, I would return to New York and, dressed in white tie and tails or tuxedo, attend nine “coming out” parties or debutante balls. I felt important hobnobbing with the Rockefeller children, being among the “right people.” But even though I was in the midst of organdy and corsages, I would often end up off at one side of the Waldorf-Astoria ballroom, feeling separate and desolate.

Eli Siegel is the person who had the knowledge and good will to identify the greatest scourge of humanity: our desire to be important through contempt, which he defined as “the lessening of what is different from oneself as a means of self-increase as one sees it.” In his lecture Mind and Importance, he explains:

To be selfish in the bad sense means that you are important at the expense of other people’s importance: you are the only important thing in sight and you are going to get your importance even if other people are made unimportant.

In an Aesthetic Realism lesson, Mr. Siegel kindly showed how this false notion of importance was working in me, so that I could change. He asked me:

When you meet somebody who doesn’t have the privileges that you have, how should you see that person?…Did you have contempt?…The basis is the feeling that since we exist, the only way to maintain [ourselves] is to be better than anything else, no matter what happens. It’s the worst possibility of human nature.

This possibility of human nature pervaded our family hearth and showed in the way we spoke about people. I remember, for instance, a song that we enthusiastically sang as a round on family car trips:

Lowly though they be,

Lowly though they be,

Let us not deny our friends

Because of poverty.

We enjoyed the tune without thinking of the words as anything else but a joke; but the patronizing and brutally unjust way of seeing people that the words represent nearly ruined my life. I regret so much the centuries-old injustice done to millions of people that I took part in: the feeling that it was all right for some people to be poor while others had wealth. And it means so much to me that today I know the most important question about a human being; it was asked by Eli Siegel: “What does a person deserve by being a person?”

Before I met Aesthetic Realism, I thought the less emotion I had, the more important I would be. Coolness and restraint were, I thought, signs of my natural superiority over anyone or anything that tried to affect me. Mr. Siegel so kindly taught me that this desire to be contemptuously impervious to things made me empty, dull, and incapable of having the emotions I was born to have. He explains further in Mind and Importance:

We would rather be important by suffering than “unimportant” and happy….If any person were asked plainly, “Would you like to lose some of your importance and be happier?” he’d say yes—but it doesn’t work out that way. We would rather be miserable and think we’ve got ourselves and can lessen other things.

And in the lecture he gives the basis for true importance:

If you are important because you feel that what’s real is important, that other people can be important, and that you are important because you are a particular way of seeing those things; and if through the respect or importance you give yourself, you have a tendency to give more meaning to what is not yourself—then your importance is good.

The knowledge of what real importance is has changed the course of my whole life. I am now able to have large feelings about people that were not possible before I met Aesthetic Realism, feelings without which I would not be wholly alive. Mr. Siegel once said to me: “Not to have a (true) emotion would be the same as going into one’s grave before the undertaker knew what he was about!”

Now, I have great emotion about the world, and I have true, great emotion about my wife, Sally Ross, who is a high school biology teacher. I treasure being married to her, and am so proud that being close to her has me feel closer to other people and care for them more. And I am grateful that both of us are studying in magnificent classes taught by Ellen Reiss, Aesthetic Realism Chair of Education, and learning from her what it means to have emotions about the world and people that make a person truly important.

II. Importance in a Renowned Actor

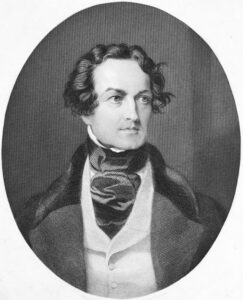

National Portrait Gallery, London

A man in theatrical history who had both true and false importance is the Shakespearean actor William Charles Macready, born in 1793 to parents who were actors themselves. As a young man, his father left Dublin for London, where he worked in theatrical productions as a “Walking Gentleman,” or walk-on. He eventually became a theatre manager, but sent his son to the prestigious school Rugby; he wanted William to go to Oxford and become a respectable member of the bar, not an actor.

At the time, the reason for his preference was not so surprising. A theatrical historian, William Prynne, in 1633 described actors as “the very dregs of men; the shame, the blemish of our English Nation…the very instrument of sinne and Satan.” Though many decades had passed, this way of seeing persisted.

In the book The Shakespeare Riots, Nigel Cliff writes that when a headmaster at Rugby asked William, “Are you quite certain you should not wish to go on the stage?” the boy replied, “Quite certain, sir; I very much dislike it, and the thought of it.” But young William was forced to go to work in the theatre because his father went bankrupt and was thrown into debtors’ prison. William’s mother had died in childbirth, and he needed to make money to get his father out. So with great trepidation he made his debut as Romeo in Birmingham in 1810. He was only seventeen.

Unlike Macready, I was drawn to the theatre enough to leave Yale engineering school in order to get a Fine Arts degree in Theatre. I mainly studied the technical aspects, and eventually the business end of theatre. I had great pleasure coming up with innovative solutions to problems—such as how to have it rain real water at a theatre-in-the-round in Michigan; how to design lighting so that it would show the actors at their best—I was proud when the famous actress Tallulah Bankhead said my work made for “the nicest stage lighting I had had all summer”; and how to rig the lights in a proscenium tent theatre so that, at a dramatic moment in the murder mystery The Mousetrap, an actor could—with the flick of a switch—plunge the stage into darkness. These were ways I had good importance, because I was using my mind on behalf of being exact, trying to be just to an aspect of reality and art.

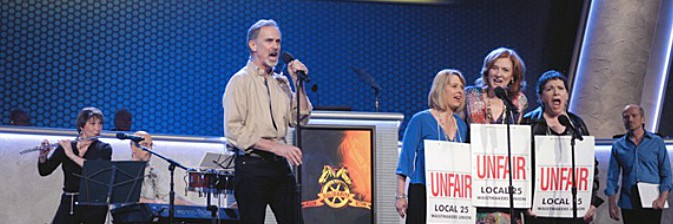

And during workshop productions at college I made a discovery that greatly surprised me: I found that as I studied to portray a character on stage, I was able to have emotions I didn’t seem capable of having in my everyday life. Mr. Siegel told me later in an Aesthetic Realism class that one of the great purposes of life is to have emotions one can be proud of. I was thrilled! I’m proud of the true importance my life has now through being part of the Aesthetic Realism Theatre Company—the company that presents productions based on Eli Siegel’s mighty comprehension of drama and music, and sees acting as a means of being just to the world.

In early 19th century England only two theatres were given “patents” or legal permission to exist—the Drury Lane and the Covent Garden. The majority of the illegal theatres presented what were called “burlettas,” which included sentimental melodramas with songs, light operas, pantomimes, broad farces, and even performing animals. The patent theatres, each having a capacity of 3000 people, specialized in spectacles: ships blew up and sank, buildings burned, and fire engines clattered across the stage.

Theatre managers at the time wielded great power over actors, controlling their salaries, and the roles and plays they performed in. Because Macready wanted actors to be treated with more respect, he himself became the manager of the Covent Garden Theatre in 1837, where he also appeared in leading roles, such as King Lear, Macbeth, and Hamlet.

Macready established innovations that became famous. He was very strict about rehearsals and introduced high standards of scenery and costume based on thorough historical research. In those years, productions of Shakespeare took great liberties with the scripts, but Macready insisted on close study of the original scripts; his respect for Shakespeare was very large.

And he was truly important in that he revised the whole style of acting, making it less artificial. To do so, he had to go against his early training, which included a singsong style of declamation and elaborate gestures. To avoid these, he actually set up mirrors in his home, tied his hands to his sides and practiced Shakespearean monologues, training himself to show passion through his facial expressions and his eyes.

In the biography The Eminent Tragedian, Alan S. Downer writes,

[I]t was [Macready’s] often repeated belief that he did not act well if he had not identified himself with his character…. [H]is daughter Katie once [told of] the solemn way in which her father declared that a certain action of Antonio, in the Merchant [of Venice], was very kind. He seemed, she said, to think Antonio was alive. “And so he is to me,” Macready replied, “So are they all. Who is alive if they are not?”

This way of seeing acting is beautiful and has ethics in it. Macready wanted to get deeply within the self, the life of the character he was portraying, and it made him one of the great Shakespearean actors.

He was also very fortunate in having some of the most important friends and advisors: Lord Byron, Robert Browning, Bulwer-Litton, and Charles Dickens. In fact, Dickens was a great admirer of Macready; and the two families regularly vacationed together.

But William Macready also went after importance based on ego, particularly in his fierce rivalry with Edwin Forrest, the first great American actor, about whom my colleague, Bennett Cooperman, has written.

The styles of the two actors were quite different: Forrest’s acting was rugged and more spontaneous while Macready’s was more dignified and scholarly. They were once friends but later became adversaries, and were even known to have hissed each other’s performances in public. The desire for cheap importance had by actors and non-actors alike, which Ellen Reiss describes in The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, did not escape them. She writes::

Contempt in people hates the idea that anything or anyone should be bigger than oneself. Contempt says…”The way for me to be big is to feel someone else is small. If I can see you as less than I am,…that makes me big. But if I have to see you as having largeness, if I have to look up to you, then I’m small—I’m nothing.

III. A Young Man Learns about Importance in Aesthetic Realism Consultations

The matter of what makes importance good or bad has been central in the Aesthetic Realism consultations of John Roland, a buyer for a large electronics store. Mr. Roland could charm people with his ready smile and easy manner, but this ability had also caused difficulty with co-workers, who, he told us, objected to the way he put himself forth. He himself wanted to change but didn’t know how. “One moment I can sit down and have a real conversation with somebody,” he said, “and the next minute I can be very superficial and joking.” We asked him:

Consultants. Do you have a fight between wanting to be serious, thoughtful and wanting to have a big effect on people?

Jonh Roland. Yes, I do.

Consultants. And do you think this can mix other people up?

JR. Yes, definitely.

Consultants. We’re interested in having you be an integrity in how you see people—that there are not two John Rolands wandering around not knowing which one is going to come forth. Either your purpose is to knock people off their feet and show how brilliant you are, what a sparkling, debonair personality you have, or you’re going to feel that doing all you can to know what another person feels is good for you, makes you more.

JR. That’s what I want.

Consultants. We want you to see people as deeply as possible so that you can be most useful and have a good effect. You have a chance to learn and be in new territory. We think you should take it.

JR. I’m going to.

IV. What False Importance Can Lead To

On Macready’s third tour in the US, which was meant to be a triumphant final tour, Edwin Forrest booked himself into rival theatres all along the way to play the same Shakespearean roles as Macready. In a lecture Mr. Siegel gave, titled People Have Objected in History, he explained that Forrest “stood for American self-esteem” and that when he was hissed in London, “America did not like it.” This ugly competition between two fine actors climaxed when they were to play at theatres close to each other at Astor Place in New York. This is an account of what happened:

Macready appeared in New York in 1849….[Anger at the insult to Forrest]…prompted a demonstration against Macready so violent that the Governor of New York called out troops to protect him.

Inside the theatre the stage was bombarded with eggs, furniture, chairs, while the audience yelled so loudly that none of the actors could be heard. Outside, an angry crowd of people hurled paving stones at the soldiers, and an officer gave the command for the troops to fire, causing many people to be killed. This tragic event, known as the Astor Place Riots, shows how far the battle for importance based on contempt can go.

Meanwhile, the art of Macready came from something very different—his desire to be so fair to the depths of a character, that the character came alive and stirred audiences greatly. For this he is important in the history of the theatre.

The great good news about importance, the thing every person needs to know, Mr. Siegel explains in his lecture Mind and Importance:

If we make ourselves important in a way that looks lovely to us, that is not unfair to anyone else—that is what life wants…. [E]very self seen truly, as it is, is important. That is one of the fundamental statements of Aesthetic Realism.